Type II SLAP Lesions in Overhead Athletes: Why the High Failure Rate?

By: William B. Stetson, M.D.

Superior labral anterior to posterior (SLAP) tears in overhead athletes can be a career-ending injury because of the high failure rates with surgical intervention. Smith et al.1 identified 24 MLB pitchers reporting surgery for a SLAP tear and found that 63% returned to play in the major leagues. The results are even worse in other studies of baseball pitchers, with rates varying from 7-62%.2-9

We must ask ourselves: Why the poor results and high failure rates in overhead athletes with Type II SLAP repairs? Is it the failure to establish the diagnosis of these athletes preoperatively, and as a result not treating them with an adequate nonoperative regimen before considering surgery? Or is it the operating surgeon’s inability to differentiate normal anatomic variants from SLAP lesions during the time of surgery? Is it the surgical technique that violates the rotator cuff or the improper placement of suture anchors, which restricts range of motion postoperatively and disrupts overhead throwing mechanics?10 Or is it inadequate postoperative rehabilitation? We will briefly address each one of these by dissecting the literature. Hopefully, this conversation will stir further debate and lead to a better understanding of SLAP lesion treatment in overhead athletes.

Failure to Establish the Correct Diagnosis. The diagnosis of isolated SLAP lesions is historically difficult. This is attributed to several reasons such as the high incidence of other associated pathology. Studies of SLAP lesions suggest that most patients have pain, mechanical symptoms, range of motion loss (most notable) or the inability to perform at their previous activity level.11, 12 When occurring in throwing athletes, SLAP lesions present an additional layer of complexity when evaluating the throwing shoulder. Through repetitive stress, elite throwers develop osseous and ligamentous adaptive changes, allowing them to reach extremes of external rotation.13 The biggest difficulty is differentiating a symptomatic SLAP lesion from degenerative labrum changes or even normal variants. Most SLAP lesions occur in the dominant arm of high-level male overhead athletes who are younger than 40 years old.14 Patients older than 40 years of age often have degenerative labrum changes which may or not be clinically significant or pathologic.15 There is currently no sensitive clinical examination test for SLAP lesions, as many other pathologic conditions are associated with SLAP lesions. A high index of suspicion is necessary to accurately diagnose and treat these injuries.

Inadequate Nonoperative Management. An MRI or an MR Arthrogram showing a SLAP lesion is not an automatic indication for surgery.10 In our prospective study of U.S. Olympic Volleyball athletes, 46% of asymptomatic elite volleyball players had MRI evidence of SLAP tears but no history of shoulder problem complaints.16 SLAP tears are also identified on MRI in up to 48% of pitchers who are asymptomatic.17, 18 These studies show that pathologic MRI findings in elite overhead athletes can be present; however, they are often asymptomatic. In competitive overhead athletes such as volleyball players or baseball pitchers, MRI or MR Arthrogram evidence of a SLAP lesion may not be the cause of their shoulder pain and can initially be treated with nonoperative management. Frequently, superior labrum injuries can be successfully treated with a well-structured and carefully implemented nonoperative rehabilitation program. The key to successful nonoperative treatment is a thorough history, clinical examination and accurate diagnosis.19 Typical nonoperative treatments have centered on posterior capsular stretching while maintaining glenohumeral as well as periscapular strength and stability.20

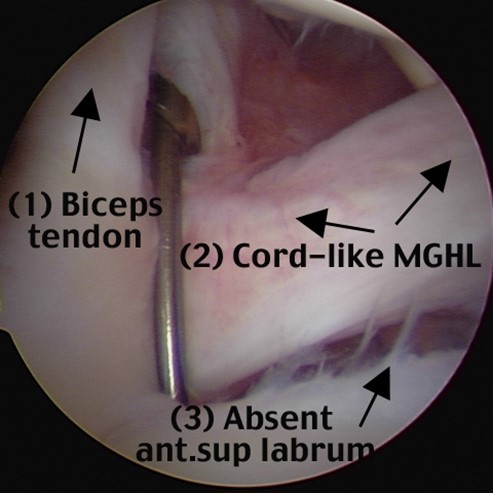

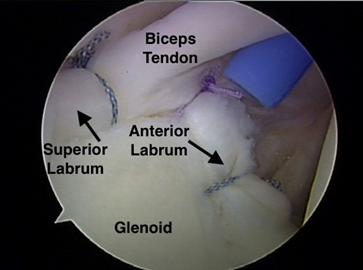

Surgical Repair of Normal Variants. If our overhead athletes have failed nonoperative management, diagnostic arthroscopy with possible surgical repair is the next step in treatment. At the time of diagnostic arthroscopy, we perform a complete 15-point diagnostic shoulder arthroscopy of the glenohumeral joint21 and evaluate treatment of all pathology. SLAP tears rarely occur in isolation, and studies show that associated pathology occurs in 72-88% of throwing shoulders.22, 12 The superior labrum is part of this diagnostic examination. Careful attention needs to be made to differentiate a meniscoid-type of labrum from a Type II SLAP tear, as well as a normal Buford complex from a pathologic or torn anterior superior labral tear (Figure 1) and a normal sublabral foramen (Figure 2). This has proven to be difficult even among experienced shoulder surgeons. In a study by Gobezie et al.23 of fellowship-trained “expert shoulder surgeons,” only 48% correctly identified a Type II SLAP lesion with poor inter- and intra-observer reliability. Repairing a meniscoid-type of labrum or a normal labral variant can lead to a loss of external rotation, which can limit the ability of an overhead athlete to return to peak form.

Improper Surgical Technique. SLAP repair in overhead athletes has yielded poor results and does not return most athletes to their previous level of play.24, 3, 7, 25, 26 There is controversy as to the proper surgical technique and anchor placement for Type II SLAP repairs. Several biomechanical studies of Type II SLAP lesions have investigated various techniques of suture anchor placement to determine the correct repair construct. There remains no consensus on the most ideal technique for Type II SLAP repairs.27 However, it is apparent that some anchor and suture configurations are less efficacious than others when looking at the biomechanical studies that were performed followed by the clinical studies.

Bacdini et al.28 compared a single-loaded suture anchor versus a double-loaded suture anchor repair and found no difference in pull-out strength. Yoo et al. determined that a mattress suture technique was inferior to a simple suture technique regarding clinical failure.29 In contrast, the mattress suture was noted to be biomechanically superior to simple suture configurations for a biceps anchor repair by Domb et al.30 Several studies show that the one well-placed anchor is biomechanically sufficient28, 30 and multiple anchors usually are not necessary. Domb et al.30 concluded that a single anchor with a mattress suture may be the most biomechanically advantageous construct for Type II SLAP repairs.

Cadaveric and biomechanical studies by McCulloch, Andrews and colleagues determined that an anchor anterior to the biceps tendon had the greatest effect in decreasing external rotation.13 Avoiding the use of an anchor anterior to the biceps should be considered especially in baseball players and other overhead athletes, where even such a small loss of external rotation would be detrimental13 (Figure 3). Burkart, Morgan and colleagues suggested that in Type II SLAP repairs, a suture anchor just posterior to the biceps insertion is the most important in resisting peel back forces during late cocking.31 This is supported by a biomechanical study that shows a single anchor placed just posterior to the biceps eliminated the peel back of the labrum.32

Violation of the rotator cuff at the time of arthroscopic surgical repair was also shown to lead to poor results in three different studies of overhead athletes.33-35 Each of these studies used a “trans rotator cuff portal,” or the so-called Port of Wilmington, with a cannula through the musculotendinous junction of the rotator cuff for anchor placement. This portal was associated with poor results of 13%6, 38%8 and 44%36 who were able to return to their preinjury level of throwing. We do not recommend this technique of violating the rotator cuff for anchor placement, especially with a large diameter cannula. Rather, the technique of a single anchor placed via a cannula through the rotator interval is preferred.

Biceps tenodesis is a proposed alternative or adjunct to SLAP repair.24, 37, 38 The kinematic consequences of biceps tenodesis within the pitching motion remain largely unknown.39 A SLAP repair preserves the glenohumeral function of the long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT), whereas biceps tenodesis removes the intra-articular portion of the LHBT and, along with it, any function that this tendon may cause in glenohumeral kinematics.39

Associated Shoulder Pathology. SLAP lesions rarely occur in isolation and can be associated with other shoulder disorders. These injuries often occur with other shoulder pathology such as impingement, partial rotator cuff tears and instability. SLAP lesions were identified in association with shoulder instability but can occur in association with diagnoses other than instability.40, 11, 41-43 According to Neri et al.,6 the inability to return to preinjury level of competition correlated with the presence of a partial-thickness rotator cuff tear. In this study of overhead throwing athletes, only 13% of athletes with partial-thickness, articular-sided rotator cuff tears (less than 50% treated with debridement) were able to return to their preinjury level of competition.6 With such a high failure rate, more aggressive treatment (partial articular supraspinatus tendon avulsion, or PASTA, repair versus completing the tear and repair) of the partial-thickness rotator cuff tear is necessary.

Failure to Rehab Properly. As surgeons, we are responsible for our patients throughout the entire continuum of surgical care, which includes the entire postoperative period. The so-called Cut and Run where surgeons have minimal, if any, involvement in the postoperative care of their patients is unacceptable. We must be leaders of the postoperative team that coordinates and guides the physical therapists and patients through this period until patients return to their optimum level of performance.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

Establish the Correct Diagnosis. Studies of SLAP lesions suggest that most patients have pain, mechanical symptoms, range of motion loss (most notable) or inability to perform at their previous activity level.11, 12

Nonoperative Management. An MRI or an MR Arthrogram showing a SLAP lesion is not an automatic indication for surgery. A complete course of nonoperative management for patients prior surgery is recommended.

Surgical Repair of Normal Variants. Knowing your anatomy and normal labral variants are paramount in surgical repair. Repairing a meniscoid-type of labrum, Buford complex or a normal sublabral foramen variant can lead to external rotation loss which can limit the ability of an overhead athlete to return to peak form.

Surgical Technique. A well-placed single anchor posterior to the biceps tendon is all that is necessary for surgical repair and will not lead to external rotation loss. Use of the rotator interval portal and avoiding the “trans rotator cuff portal” will limit rotator cuff damage and lead to better results.

Associated Shoulder Pathology. SLAP lesions rarely occur in isolation. Be prepared to address other surgical pathology including partial rotator cuff tears.

Failure to Rehab Properly. Avoid the Cut and Run surgical mentality and be the leader of the postoperative team along with the physical therapists and athletic trainers.

- Smith, R., Lombardo, D.J., Petersen-Fitts, G.R., Frank, C., Tenbrunsel, T., Curtis, G., Whaley, J., Sabesan, V.J. “Return to Play and Prior Performance in Major League Baseball Pitchers After Repair of Superior Labral Anterior-Posterior Tears.” Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 2016;4(12):2325967116675822.

- Fedoriw, W.W., Ramkumar, P., McCulloch, P.C., Linter, D.M. “Return to Play After Treatment of Superior Labral Tears in Professional Baseball Players.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2014;42:1155-1160.

- Kim, S.H., Ha, K.I., Kim, S.H., Choi, H.J. “Results of Arthroscopic Treatment of Superior Labral Lesions.” The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery – American Volume. 2002;84:981-985.

- Park, S., Glousman, R.E. “Outcomes of Revision Type II Superior Labral Anterior Posterior Repairs.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2011;39(6):1290-1294.

- Pagnani, M.J., Speer, K.P., Altchek, D.W., Warren, R.F., Dines, D.M. “Arthroscopic Fixation of Superior Labral Lesions Using a Biodegradable Implant: A Preliminary Report.” Arthroscopy. 1995;11(2):194-198.

- Neri, B.R., ElAttrache, N.S., Owsley, K.C., Mohr, K., Yocum, L.A. “Outcome of Type II Superior Labral Anterior Posterior Repairs in Elite Overhead Athletes: Effect of Concomitant Partial-Thickness Rotator Cuff Tears.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2011;39:114-120.

- Ide, J., Maeda, S., Takagi, K. “Sports Activity After Arthroscopic Superior Labrum Repair Using Suture Anchors in Overhead Athletes.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2005;33(4)507-514.

- Cohen, D.B., Cleman, S., Drakos, M.C. et al. “Outcomes of Isolated Type II SLAP Lesions Treated With Arthroscopic Fixation Using a Bioabsorbable Tack.” Arthroscopy 2006;22(2):136-142.

- Gilliam, B., Douglas, L., Fleisig, G., Aune, K., Mason, K., Dugas, J., Cain, L., Ostrander, R., Andrew, J. “Return to Play and Outcomes in Baseball Players After Superior Labral Anterior-Posterior Repairs.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2018;46(1):109-115.

- Stetson, W.B., Polinsky, S., Morgan, S.A., Strawbridge, J., Carcione, J. “Arthroscopic Repair of Type II SLAP Lesions in Overhead Athletes.” Arthroscopy Techniques. 2019;8(7):e781-792.

- Maffet, M.W., Gartsman, G.M., Moseley, B. “Superior Labrum-Biceps Tendon Complex Lesions of the Shoulder.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 1995;23(1):93-98.

- Snyder, S.J., Banas, M.P., Karzel, R.P. “An Analysis of 140 Injuries to the Superior Glenoid Labrum.” Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 1995;4(4):243-248.

- McCulloch, P.C., Andrews, W.J., Alexander, J., Brekke, A., Duwani, S., Noble, P. “The Effect on External Rotation of an Anchor Placed Anterior to the Biceps in Type II SLAP Repairs in a Cadaveric Throwing Model.” Arthroscopy. 2013;29:18-24.

- Rapley, J.H., Barber, F.A. “Chapter 14: Superior Labrum Anterior and Posterior (SLAP) Tears.” AANA Advanced Arthroscopy: The Shoulder, Elsevier, Inc., 2010, pp. 177-187.

- Rapley, J.H., Barber, F.A. “Chapter 4: Labral (Including SLAP) Lesions: Classification and Repair Techniques." Sports Medicine. 2013;1(4)(Suppl 1). Johnson, D.H., editor-in-chief. Operative Arthroscopy Fourth Edition, Wocters Klower, 2003, pp. 149-159.

- Lee, C.S., Goldhaber, N.H., Powell, S.E., Stetson, W.B. “Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings in Asymptomatic Elite Overhead Athletes.” Arthroscopy. 2017;33(10):58-59.

- Lee, S.B., Kim, K.J., O'Driscoll, S.W., Morrey, B.F., An, K.N. “Dynamic Glenohumeral Stability Provided by the Rotator Cuff Muscles in the Mid-Range and End-Range of Motion: A Study in Cadavers.” The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery – American Volume. 2000;82(6):849-857.

- Sheridan, K., Kreulen, C., Kim, S., Mak, W., Lewis, K., Marder, R. “Accuracy of Magnetic Resonance Imaging to Diagnose Superior Labrum Anterior Posterior Tears.” Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2015;23(9):2645-2650.

- Wilk, K.E., Meister, K., Andrews, J.R. “Current Concepts in the Rehabilitation of the Overhead Throwing Athlete.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2002;30(1):136-151.

- Edwards, S.L., Lee, J.A., Bell, J.E. et al. “Nonoperative Treatment of Superior Labrum Anterior to Posterior Tears.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2010;38(7):1456-1461.

- Snyder, S.J. Shoulder Arthroscopy, Second Edition. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2003.

- Kim, T., Queale, W., Cosgarea, A., McFarland, E. “Clinical Features of the Different Types of SLAP Lesions: An Analysis of 139 Cases.” The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery – American Volume. 2003; 85(1):66-71.

- Gobezie, R., Zurakowski, D., Lavery, K., Millett, P.J., Cole, B.J., Warner, J.J. “Analysis of Interobserver and Intraobserver Variability in the Diagnosis and Treatment of SLAP Tears Using the Snyder Classification.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2008;36(7):1373-1379.

- Boileau, P., Parrot, S., Chuinard, C., Rousanne, Y., Shia, D., Bicknell, R. “Arthroscopic Treatment of Isolated Type II SLAP Lesions: Biceps Tenodesis as an Alternative to Reinsertion.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2009;37(5):929-936.

- Edwards, S.L., Lee, J.A., Bell, J.E. et al. “Nonoperative Treatment of Superior Labrum Anterior to Posterior Tears.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2010;38(7):1456-1461.

- Enad, J.G., Gaines, R.J., White, S.M., Kurtz, C.A. “Arthroscopic Superior Labrum Anterior Posterior Repair in Military Patients.” The Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 2007;16(3):300-305.

- Bodulla, M.R., Adamson, G.J., Gupta, A., McGarry, M.H., Lee, T.Q. “Restoration of Labral Anatomy and Biomechanics After Superior Labral Anterior Posterior Repair: Comparison of Mattress Versus Simple Suture Technique.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2012;40:875-881.

- Baldini, T., Snyder, R.L., Peacher, G., Bach, J., McCarty, E. “Strength of Single- Versus Double-Anchor Repair of Type II SLAP Lesions: A Cadaveric Study.” Arthroscopy. 2009;25(11):1257-1260.

- Yoo, J.C., Ahn, J.H., Lee, S.H., Lim, H.C., Choi, K.W., Bae, T.S., Lee, C.Y. “A Biomechanical Comparison of Repair Techniques in Posterior Type II Superior Labral Anterior and Posterior (SLAP) Lesions.” Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 2008;17(1):144-149.

- Domb, B.G., Ehteshami, J.R., Shindle, M.K. “Biomechanical Comparison of Three Suture Anchor Configurations for Repair of Type II SLAP Lesions.” Arthroscopy. 2007;23(2):135-140.

- Burkhart, S.S., Morgan, C.D., Kibler, W.B. “The Disabled Throwing Shoulder: Spectrum of Pathology Part I: Pathoanatomy and Biomechanics.” Arthroscopy. 2003;19(4):404-420.

- Seneviratne, A., Montgomery, K., Bevilacqua, B., Zikria, B. “Quantifying the Extent of a Type II SLAP Lesion Required to Cause Peel Back of the Glenoid Labrum: A Cadaveric Study.” Arthroscopy. 2006;22(11):1163:e1-6.

- Neri, B.R., ElAttrache, N.S., Owsley, K.C., Mohr, K., Yocum, L.A. “Outcome of Type II Superior Labral Anterior Posterior Repairs in Elite Overhead Athletes: Effect of Concomitant Partial-Thickness Rotator Cuff Tears.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2011;39:114-120.

- Cohen, D.B., Cleman, S., Drakos, M.C. et al. “Outcomes of Isolated Type II SLAP Lesions Treated With Arthroscopic Fixation Using a Bioabsorbable Tack.” Arthroscopy. 2006;22(2):136-142.

- Enad, J.G., Gaines, R.J., White, S.M., Kurtz, C.A. “Arthroscopic Superior Labrum Anterior Posterior Repair in Military Patients.” Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 2007;16(3):300-305.

- Park, J.G., Cho, N.S., Kim, J.Y., Song, J.H., Hong, S.J., Rhee, Y.G. “Arthroscopic Knot Removal for Failed Superior Labrum Anterior Posterior Repair Secondary to Knot-Induced Pain.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2017;45(11):2563-2568.

- Chalmers, P., Erickson, B., Verma, N., D’Angelo, J., Romeo, T. “Incidence and Return to Play After Biceps Tenodesis in Professional Baseball Players.” Arthroscopy. 2018;34(3):747-751.

- Chalmers, P.N., Trombley, R., Cip, J., et al. “Postoperative Restoration of Upper Extremity Motion and Neuromuscular Control During the Overhand Pitch: Evaluation of Tenodesis and Repair for Superior Labral Anterior Posterior Tears.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2014;42(12):2825-2836.

- Provencher, M.T., LeClere, L.E., Romeo, A.A. “Subpectoral Biceps Tenodesis.” Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review. 2008;16(3):170-176.

- Snyder, S.J., Karzel, R.P., Del Pizzo, W., Ferkel, R.D., Friedman, M.J. “SLAP Lesions of the Shoulder.” Arthroscopy. 1990; 6(4):274-279.

- Handelberg, F., Willems, S., Shahabpour, M., Huskin, J.P., Kuta, J. “SLAP Lesions: A Retrospective Multicenter Study.” Arthroscopy. 1998;14(8):856-862.

- Musgrave, D.S., Rodosky, M.W. “SLAP Lesions: Current Concepts.” American Journal of Orthopedics (Belle Mead, N.J.) 2001;30(1):29-38.

- Mileski, R.A., Snyder, S.J. “Superior Labral Lesions in the Shoulder: Pathoanatomy and Surgical Management.” Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 1998;6(2):121-131.

Figure 1 – A right shoulder viewing from posterior to anterior in the lateral decubitus position, with a cord-like middle glenohumeral ligament, absent anterior superior labrum and so-called Buford complex.

Figure 2 – A right shoulder viewing from posterior to anterior in the lateral decubitus position with a normal sublabral foramen.

Figure 3 – A right shoulder viewing from posterior to anterior in the lateral decubitus position with multiple sutures placed anterior to the biceps tendon, which capture the superior glenohumeral ligament and restrict external rotation. This technique should be avoided.